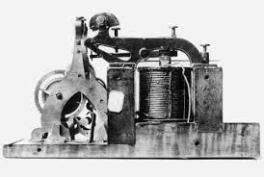

In 1832 Samuel F. B. Morse, assisted by Alfred Vail, conceived of the idea for an electromechanical telegraph, which he called the “Recording Telegraph.” This commercial application of electricity was made tangible by their construction of a crude working model in 1835-36. This instrument probably was never used outside of Professor Morse’s rooms where it was, however, operated in a number of demonstrations.

In 1832 Samuel F. B. Morse, assisted by Alfred Vail, conceived of the idea for an electromechanical telegraph, which he called the “Recording Telegraph.” This commercial application of electricity was made tangible by their construction of a crude working model in 1835-36. This instrument probably was never used outside of Professor Morse’s rooms where it was, however, operated in a number of demonstrations.

The telegraph was further refined by Morse, Vail, and a colleague, Leonard Gale, into working mechanical  form in 1837. In this year Morse filed a caveat for it at the U.S. Patent Office. Electricity, provided by Joseph Henry’s 1836 “intensity batteries,” was sent over a wire. The flow of electricity through the wire was interrupted for shorter or longer periods by holding down the key of the device. The resulting dots or dashes were recorded on a printer or could be interpreted orally. In 1838, Morse perfected his sending and receiving code and organized a corporation, making Vail and Gale his partners.

form in 1837. In this year Morse filed a caveat for it at the U.S. Patent Office. Electricity, provided by Joseph Henry’s 1836 “intensity batteries,” was sent over a wire. The flow of electricity through the wire was interrupted for shorter or longer periods by holding down the key of the device. The resulting dots or dashes were recorded on a printer or could be interpreted orally. In 1838, Morse perfected his sending and receiving code and organized a corporation, making Vail and Gale his partners.  In 1843, Morse received funds from Congress to set up a demonstration line between Washington and Baltimore. Unfortunately, Morse was not an astute businessman and had no practical plan for constructing a line. After an unsuccessful attempt at laying underground cables with Ezra Cornell, the inventor of a trenchdigger, Morse switched to the erection of telegraph poles and was more successful. On May 24, 1844, Morse in the U.S. Supreme Court Chambers in Washington sent by telegraph the oft-quoted message to his colleague Vail in Baltimore, “What hath God wrought!”

In 1843, Morse received funds from Congress to set up a demonstration line between Washington and Baltimore. Unfortunately, Morse was not an astute businessman and had no practical plan for constructing a line. After an unsuccessful attempt at laying underground cables with Ezra Cornell, the inventor of a trenchdigger, Morse switched to the erection of telegraph poles and was more successful. On May 24, 1844, Morse in the U.S. Supreme Court Chambers in Washington sent by telegraph the oft-quoted message to his colleague Vail in Baltimore, “What hath God wrought!”  In 1845, Morse hired Andrew Jackson’s former postmaster general, Amos Kendall, as his agent in locating potential buyers of the telegraph. Kendall realized the value of the device, and had little trouble convincing others of its potential for profit. By the spring he had attracted a small group of investors. They subscribed $15,000 and formed the Magnetic Telegraph Company. Many new telegraph companies were formed as Morse sold licenses wherever he could.

In 1845, Morse hired Andrew Jackson’s former postmaster general, Amos Kendall, as his agent in locating potential buyers of the telegraph. Kendall realized the value of the device, and had little trouble convincing others of its potential for profit. By the spring he had attracted a small group of investors. They subscribed $15,000 and formed the Magnetic Telegraph Company. Many new telegraph companies were formed as Morse sold licenses wherever he could.

The first commercial telegraph line was completed between Washington, DC, and New York City in the spring of 1846 by the Magnetic Telegraph Company. Shortly thereafter, F.O.J. Smith, one of the patent owners, built a line between New York City and Boston. Most of these early companies were licensed by owners of Samuel Morse patents. The Morse messages were sent and received in a code of dots and dashes.

At this time other telegraph systems based on rival technologies were being built. Some companies used the printing telegraph, a device invented by a Vermonter, Royal E. House, whose messages were printed on paper or tape in Roman letters. In 1848, a Scottish scientist, Alexander Bain, received his patents on a telegraph. These were but two of many competing and incompatible technologies that had developed. The result was confusion, inefficiency, and a rash of suits and countersuits.

By 1851, there were over 50 separate telegraph companies operating in the United States. This corporate cornucopia developed because the owners of the telegraph patents had been unsuccessful in convincing the United States and other governments of the invention’s potential usefulness. In the private sector, the owners had difficulty convincing capitalists of the commercial value of the invention. This led to the owners’ willingness to sell licenses to many purchasers who organized separate companies and then built independent telegraph lines in various sections of the country.

Hiram Sibley moved to Rochester, New York, in 1838 to pursue banking and real estate. Later he was elected sheriff of Monroe County. In Rochester, he was introduced to Judge Samuel L. Selden who held the House Telegraph patent rights. In 1849, Selden and Sibley organized the New York State Printing Telegraph Company, but they found it hard to compete with the existing New York, Albany, and Buffalo Telegraph Company.

After this experience, Selden suggested that instead of creating a new line, the two should try to acquire all the companies west of Buffalo and unite them into a single unified system. Selden secured an agency for the extension throughout the United States of the House system. In an effort to expand this line west, Judge Selden called on friends and the people in Rochester. This eventually led in April 1851 to the organization of a company and the filing in Albany of the Articles of Association for the “New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company” (NYMVPTC), a company which later evolved into the Western Union Telegraph Company.

In 1854, there were two rival systems of the NYMVPTC in the West. These two systems consisted of 13 separate companies. All the companies were using Morse patents in the five states north of the Ohio River. This created a struggle between three separate entities, leading to an unreliable and inefficient telegraph service. The owners of these rival companies eventually decided to invest their money elsewhere and arrangements were made for the NYMVPTC to purchase their interests. Hiram Sibley recapitalized the company in 1854 under the same name and began a program of construction and acquisition. The most important take-over was carried out by Sibley when he negotiated the purchase of the Morse patent rights for the Midwest for $50,000 from Jeptha H. Wade and John J. Speed, without the knowledge of Ezra Cornell, their partner in the Erie and Michigan Telegraph Company (EMTC). With this acquisition, Sibley proceeded to switch to the superior Morse system. He also hired Wade, a very capable manager, who became his protégé and later his successor. After a bitter struggle Morse and Wade obtained the EMTC from Cornell in 1855, thus assuring dominance by the NYMVPTC in the Midwest.

In 1856, the company name was changed to the “Western Union Telegraph Company,” indicating the union of the aforementioned Western lines into one compact system. In December 1857, the Company paid stockholders their first dividend.

Between 1857 and 1861, similar consolidations of telegraph companies took place in other areas of the country so that most of the telegraph interests of the United States had merged into six systems. These were the American Telegraph Company (covering the Atlantic and some Gulf states), The Western Union Telegraph Company (covering states north of the Ohio River and parts of Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Minnesota), the New York Albany and Buffalo Electro-Magnetic Telegraph Company (covering New York State), the Atlantic and Ohio Telegraph Company (covering Pennsylvania), the Illinois & Mississippi Telegraph Company (covering sections of Missouri, Iowa, and Illinois), and the New Orleans & Ohio Telegraph Company (covering the southern Mississippi Valley and the Southwest). All these companies worked together in a mutually friendly alliance, and other small companies cooperated with the six systems, particularly some on the West Coast.

By the time of the Civil War, there was a strong commercial incentive to construct a telegraph line across the western plains to link the two coasts of America. Many companies, however, believed the line would be impossible to build and maintain.

In 1860, Congress passed, and President James Buchanan signed, the Pacific Telegraph Act, which authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to seek bids for a project to construct a transcontinental line. When two bidders dropped out, Hiram Sibley, representing Western Union, was the only bidder left. By default Sibley won the contract. The Pacific Telegraph Company was organized for the purpose of building the eastern section of the line.

Sibley sent Wade to California, where he consolidated the small local companies into the California State Telegraph Company. This entity then organized the Overland Telegraph Company, which handled construction eastward from Carson City, Nevada, joining the existing California lines, to Salt Lake City, Utah. Sibley’s Pacific Telegraph Company built westward from Omaha, Nebraska. Sibley put most of his resources into the venture. The line was completed in October 1861. Both companies were soon merged into Western Union. This accomplishment made Hiram Sibley leader of the telegraph industry.

Further consolidations took place over the next several years. Many companies merged into the American Telegraph Company. With the expiration of the Morse patents, several organizations were combined in 1864, under the name of “The U.S. Telegraph Company.” In 1866, the final consolidation took place, with Western Union exchanging stock for the stock of the other two organizations. The general office of Western Union moved at this time from Rochester to 145 Broadway, New York City. In 1875, the main office moved to 195 Broadway, where it remained until 1930 when it relocated to 60 Hudson Street.

In 1873, Western Union purchased a majority of shares in the International Ocean Telegraph Company. This was an important move because it marked Western Union’s entry into the foreign telegraph market. Having previously worked with foreign companies, Western Union now began competing for overseas business.

In the late 1870s, Western Union, led by William H. Vanderbilt, attempted to wrest control of the major telephone patents, and the new telephone industry, away from the Bell Telephone Company. But due to new Bell leadership and a subsequent hostile takeover attempt of Western Union by Jay Gould, Western Union discontinued its fight and Bell Telephone prevailed.

Despite these corporate calisthenics, Western Union remained in the public eye. The sight of a uniformed Western Union messenger boy was familiar in small towns and big cities all over the country for many years. Some of Western Union’s top officials in fact began their careers as messenger boys.

Throughout the remainder of the 1800s, the telegraph became one of the most important factors in the development of social and commercial life of America. In spite of improvements to the telegraph, however, two new inventions-the telephone (1800s) and the radio (1900s)-eventually replaced the telegraph as the leaders of the communication revolution for most Americans.

At the turn of the century, Bell abandoned its struggles to maintain a monopoly through patent suits, and entered into direct competition with the many independent telephone companies. Around this time, the company adopted its new name, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T).

In 1908, AT&T gained control of Western Union. This proved beneficial to Western Union, because the companies were able to share lines when needed, and it became possible to order telegrams by telephone. However, it was only possible to order Western Union telegrams, and this hurt the business of Western Union’s main competitor, the Postal Telegraph Company. In 1913, however, as part of a move to prevent the government from invoking antitrust laws, AT&T completely separated itself from Western Union.

Western Union continued to prosper and received commendations from the U.S. armed forces for service during both world wars. In 1945, Western Union finally merged with its longtime rival, the Postal Telegraph Company. As part of that merger, Western Union agreed to separate domestic and foreign business. In 1963 Western Union International Incorporated, a private company completely separate from the Western Union Telegraph Company, was formed and the agreement with the Postal Telegraph Company was completed. Western Union survives today.

Many technological advancements followed the telegraph’s development. The following are among the more important:

The first advancement of the telegraph occurred around 1850 when operators realized that the clicks of the recording instrument portrayed a sound pattern, understandable by the operators as dots and dashes. This allowed the operator to hear the message by ear and simultaneously write it down. This ability transformed the telegraph into a versatile and speedy system.

Duplex Telegraphy, 1871-72, was invented by the president of the Franklin Telegraph Company. Unable to sell his invention to his own company, he found a willing buyer in Western Union. Utilizing this invention, two messages were sent over the wire simultaneously, one in each direction.

As business blossomed and demand surged, new devices appeared. Thomas Edison’s Quadruplex allowed four messages to be sent over the same wire simultaneously, two in one direction and two in the other. An English automatic signaling arrangement, Wheatstone’s Automatic Telegraph, 1883, allowed larger numbers of words to be transmitted over a wire at once. It could only be used advantageously, however, on circuits where there was a heavy volume of business.

Buckingham’s Machine Telegraph was an improvement on the House system. It printed received messages in plain Roman letters quickly and legibly on a message blank, ready for delivery.

Vibroplex, about 1890, a semi-automatic key sometimes called a “bug key,” made the dots automatically. This relieved the operator of much physical strain.

Why was the telegraph so important?

Speed

-

The telegraph, invented in 1830, was a groundbreaking invention because it greatly increased the speed at which messages could be sent. Before the telegraph, long distance messages could only travel as fast as the horse or ship that carried them. Messages could take weeks to travel across the country or to Europe.

Better Communication

-

Telegraphs enabled messages to travel farther and faster than ever before. Newspaper reporters used the telegraph to send their stories to newspaper offices. During the Civil War, armies used the telegraph to send military messages between units. In 1868, Western Union Telegraph Company began sending out weather reports. By 1870, telegraph lines connected cities all over the world, from Chicago to London to Tokyo, enabling governments to communicate more quickly and efficiently.

New Services

-

The telegraph also brought about new services that had not been used before. In 1845, the first money order was sent via telegraph. In 1867, Wall Street began using the telegraph to report the purchase and sale of stocks. Railroads used the telegraph lines to create transportation networks.